Reading through Australia’s new Agriculture and Land Sector Plan, I kept waiting for the moment when it would match the ambition we’re seeing in energy and transport. It never came.

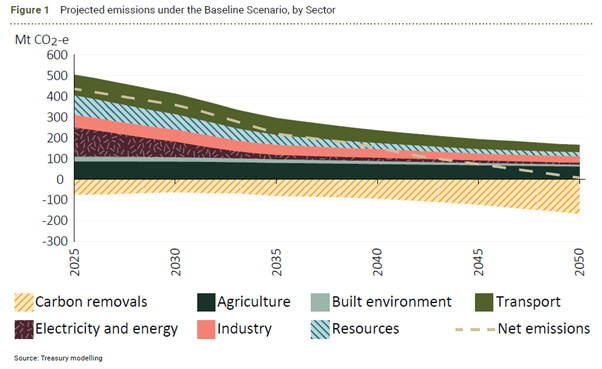

The plan projects a 28% reduction in agricultural emissions by 2050 from today. Because other sectors are decarbonising faster, agriculture will likely make up a growing share of Australia’s remaining gross emissions (37% by 2050), highlighting the challenge and importance of reducing methane and nitrous oxide in the sector.

The plan acknowledges that methane, which dominates agricultural warming, offers our best near-term opportunity to slow warming, due to its shorter atmospheric lifespan but stronger climate forcing effect. Yet the solutions proposed are mostly changes to the existing system: feed additives and a vague mention of “genetics” and “methane vaccines”.

The plan focuses almost entirely on making existing systems slightly better rather than exploring genuinely transformative approaches. There’s no consideration of cellular agriculture, which could dramatically reduce the emissions footprint of protein production. Australian company Vow just became the first to get approval to sell cellular agriculture products here. Our location makes us perfectly positioned to supply Asian markets with these emerging technologies, yet this barely gets a mention.

The efficiency gap between different protein sources is well-documented. Plant-based proteins typically require far less land, water, and energy than animal products. Supporting diversification into high-value plant proteins or new food technologies could open new opportunities and cut emissions. The plan gives limited attention to these possibilities.

What’s particularly frustrating is that agriculture is being treated as uniquely exempt from the scale of change we’re demanding everywhere else. We’re electrifying transport, revolutionising energy generation, and reimagining our built environment. The strategy for this sector relies heavily on incremental improvements, and without a broader vision it risks falling short of the kind of transformation we’ve seen in energy and transport.

I understand the challenges. Food production is essential, farmers’ livelihoods matter, dietary change is personal and complex, and livestock is a harder sector to decarbonise than electricity. But none of this should excuse us from having an honest conversation about what meaningful emissions reduction in agriculture actually requires.

Reforestation plays an important role in the plan and can create major carbon benefits. However, relying heavily on offsets risks postponing deeper changes within agricultural systems themselves. While historic, it’s worth noting that much land clearance in Australia has been for agriculture. For example, 93% of vegetation clearing in Queensland from 2018-19 was for pasture.

The sector plan reads like we’re hoping to innovate our way around fundamental inefficiencies without questioning the system itself. Other countries are investing heavily in alternative proteins and cellular agriculture. Singapore is becoming a hub for food innovation. The Netherlands announced €60 million of funding for cultivated meat and precision fermentation under the National Growth Fund. Where’s Australia’s vision for agricultural transformation?

This doesn’t mean abandoning traditional farming. It means giving producers more options and supporting them through change. It means investing in the infrastructure and research that make Australia a leader in sustainable protein production. It means taking farmers seriously as businesspeople who can adapt and thrive with the right support.

Seven years ago, I wrote about these same issues for my Per Capita Young Writers’ Prize essay. It’s disheartening to see how little the conversation has progressed. We’re still treating agricultural emissions as somehow too hard, too sensitive, or too different to tackle with the same urgency we’re bringing to other sectors.

All views expressed are my own.